What Game Designers Can Learn from Morrowind

Introduction

A road in the Ascadian Isles Region

A road in the Ascadian Isles Region

Morrowind and its two expansions, Tribunal and Bloodmoon, are now over 20 years old. Despite its recognition as one of the greatest games ever made and the grandfather of modern open-world RPGs, it’s recently earned a reputation for being hostile to newcomers and a lot of its uniquely well-designed mechanics seem to have been streamlined out of existence in modern games. So, here I am over two decades later to write a love letter to one of my favorite games, and an essay to convince a new generation of game designers and players to play — or at least appreciate — Morrowind.

If you were starting a new playthrough of Morrowind today, what could you expect? Well, the game takes a couple hours to get going. The descriptions of most spells are utter nonsense. You and an enemy can swing swords at each other point blank for ten minutes without either of hitting the other. Your character is in desperate need of prescription glasses. You will be gangstalked by Dark Brotherhood assassins the moment you set foot in Morrowind and harassed by screaming pterodactyls every minute after. Your character moves like they have cinderblocks tied to their feet. Everyone you meet is racist and walks like they’ve crapped their pants.

This is just a small sample of the many reasons people love Morrowind; of course, they’re acquired tastes. I group a lot of the above under the umbrella of “ancient cryptic RPG bullshit”. As the subliminal language of games has changed over two decades, it’s harder for modern audiences to understand what Morrowind is trying to tell them and for players to communicate in response. To get a bit more specific, I’m talking about how unfamiliar spells like Almsivi Intervention have such informative descriptions as “Almsivi Intervention on Self”. A lack of sufficient explanation is a recurring theme in Morrowind’s many role-playing systems.

But as someone who’s intimately interested in game development, I found deciphering Morrowind’s sometimes archaic gameplay to be incredibly rewarding. Playing Morrowind is like peering into to a lost era of game design. So, what techniques and ideas from the ancient days of 2002 are worth remembering?

The World

“…I have been a stranger in a strange land.”

— Exodus 2:22

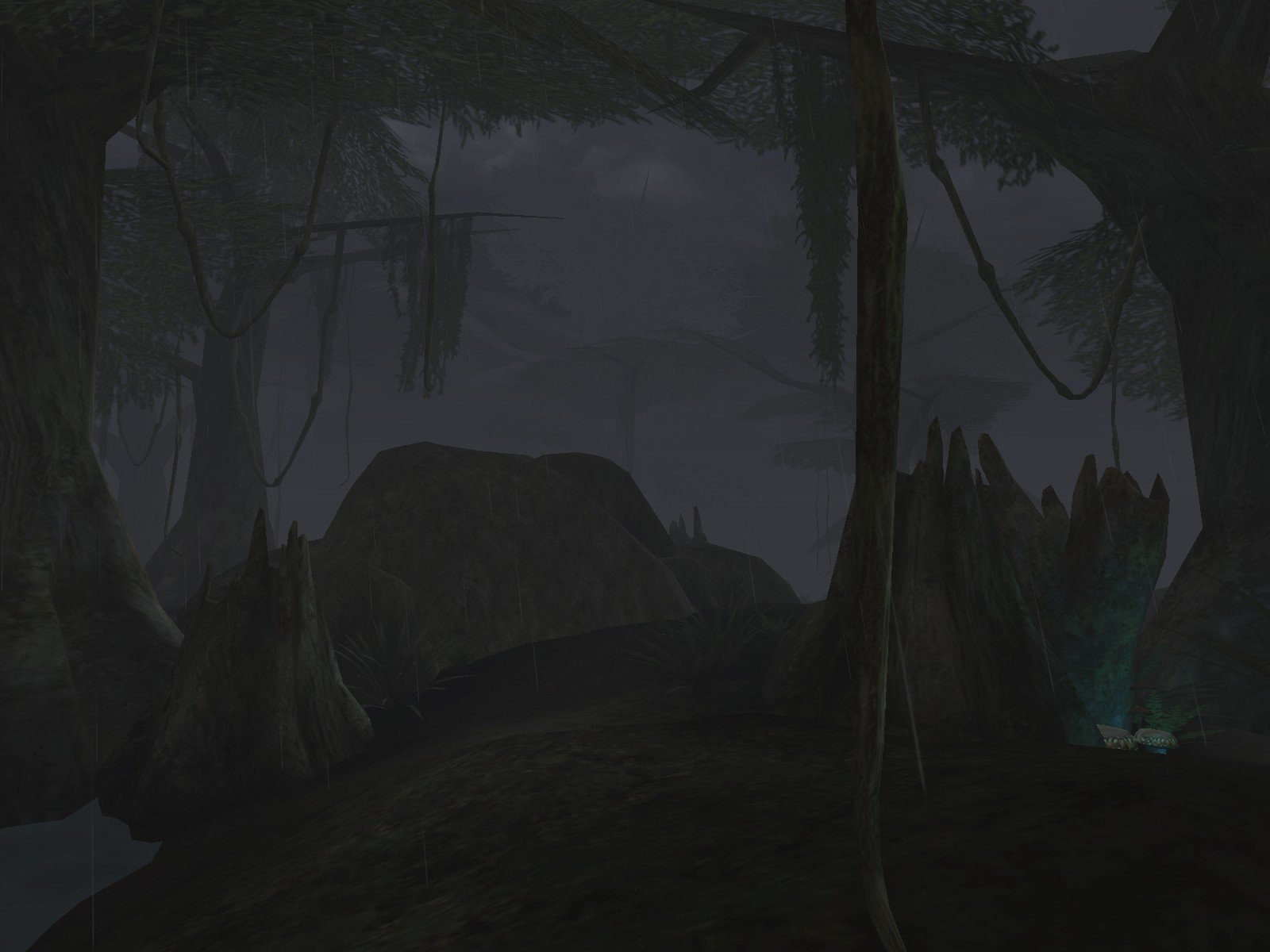

A swamp along the Bitter Coast

A swamp along the Bitter Coast

Vvardenfell — the region sub-region that the game takes place in — is a very interesting place and the skeleton on which every other aspect of the game is built. Vvardenfell’s varied regions are home to enormous ash deserts and burned trees, untamed swampy jungles, wide sloping pastures, rocky highlands, and verdant forests dotted with the enormous Emperor Parasol mushrooms. The wildlands between Morrowind’s towns and cities are home to ancestral tombs, ruins of temples to Morrowind’s spurned old gods, and Dwarven metal cities that were abandoned when the Dwemer mysteriously disappeared after the Battle of Red Mountain thousands of year ago.

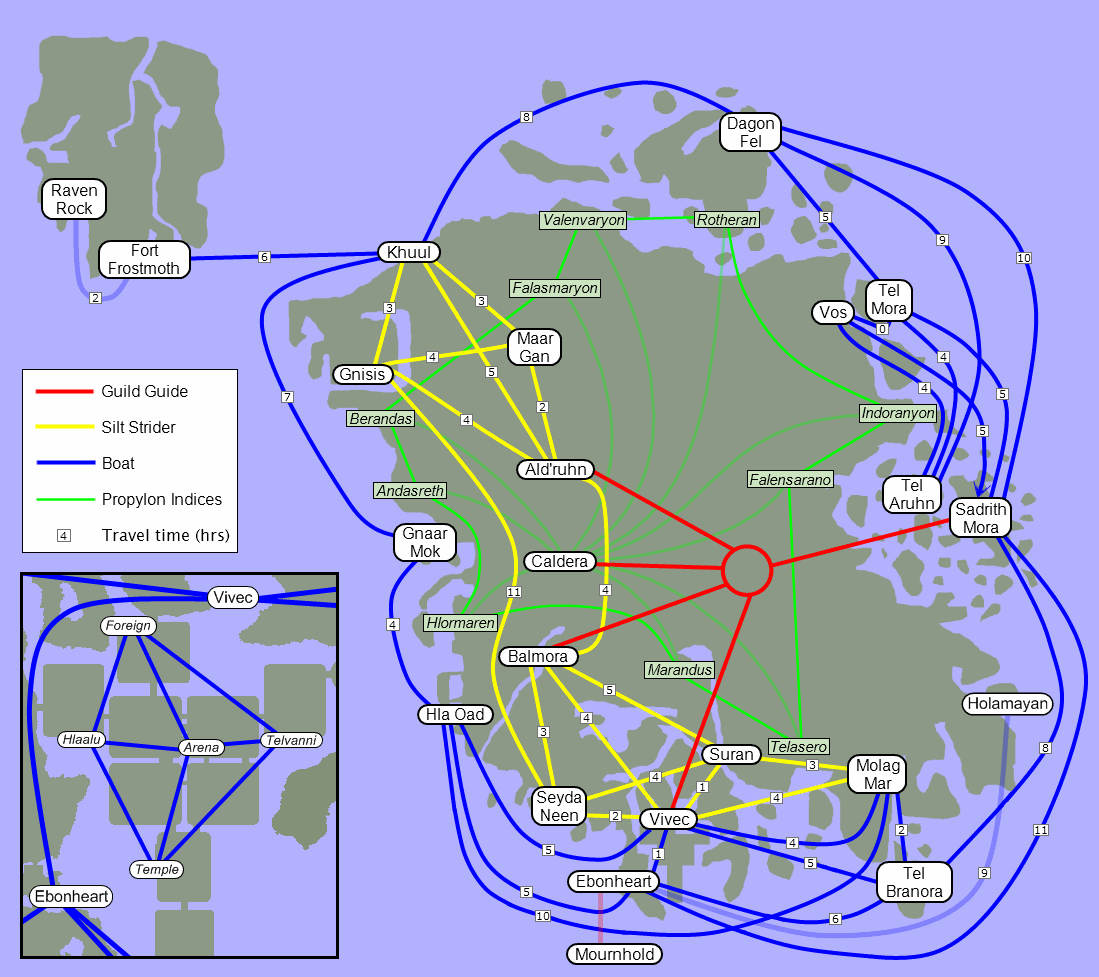

Getting around is a bit complicated. Besides the obvious option (walking), there are several different overlapping networks of fast travel stations: two boat networks, two teleportation networks, two intervention spells, silt striders, and the mark/recall spells.

Morrowind’s fast travel network. (Public domain, credit to UESP.net)

Morrowind’s fast travel network. (Public domain, credit to UESP.net)

The recall and intervention spells allow you fast travel from anywhere to an Almsivi or Imperial shrine, depending on which spell you use. Recall always returns you to the single location that you set with the Mark spell. This saves a lot of time that would otherwise be spent walking back to a town or backtracking out of a dungeon, but you’re restricted to the closest shrine; going to a specific location is the hard part.

These fast travel networks also aren’t directly connected to each other; most of them aren’t even directly connected to all of the other stations in the same network! This means, for example, that going from one coastal city to another might take several successive boat trips.

If this sounds like a hassle, it’s actually not. The process to get from one side of the map to another will take an experienced player less than 20 seconds. The point of having an intentionally inefficient fast travel network is that it forces the player to engage more deeply with the game world: to remember which towns are coastal (and will have boats), which towns have a Mage’s Guild (to teleport), if the town has a Tribunal temple or an Imperial Cult shrine, and which towns are next to each other (for Silt Striders). A town’s physical characteristics determine how easy it is to interact with the rest of the world: Dagon Fel feels like an isolated island settlement because it takes effort to get there and back, even if you’ve already been there once. Vivec City feels like a medieval metropolis in part because it has its own internal fast travel system with the gondolas plus sea, land, and teleportation routes between other major cities. It’s easy to remember that Ald’Ruhn is near Balmora because a silt strider route goes between them.

This means that the player has to make an internal map of the game world. It’s not a lot of information to remember, but it makes it feel like each point on the map exists at a specific point in space relative to everywhere else. It also means that in the journey from A to C, the player has to stop and interact with B — even just briefly — along the way. The few seconds that it takes to walk from one fast travel station to another in the same town resembles a short vignette in an Indiana Jones travel montage: going from Vos to Gnar Mok involves stepping through the wildly distinct landscapes of the Graze Lands, Azura’s Coast, Ascadian Isles, and the Bitter Coast. I plan out a route and actually travel there when I see the landscape change at each stop. This stands in contrast to Skyrim, where Riften and Markarth might as well be right next to each other and none of the features of any location actually matter.

“Why walk when you can ride?”

Morrowind’s lesson is that over-streamlining how the player travels effectively cuts out meaningful moments for the player to engage with and learn about the game world. How does the player character in Skyrim or Fallout 4 fast travel? I don’t know — the screen goes black and then they appear there. In The Witcher 3, it’s a huge challenge to make landfall in Skellige, but only the first time you go; after you see it the first time, it gets added to the magical signpost teleportation network. In Morrowind, the player character takes boats, rides giant bugs, or teleports. Morrowind’s fast travel makes the location of an area and its geographic features meaningful in how the player gets there.

The Atmosphere

“You didn’t notice it, but your brain did.”

— Red Letter Media

The slave market in Sadrith Mora

The slave market in Sadrith Mora

Morrowind’s fast travel system is intentionally inefficient beyond just needing to make multiple trips: that there are multiple large dead zones that land routes make circuitous detours to avoid. Those dead zones are related to Red Mountain, the enormous volcano at the center of Vvardenfell that represents the deadly final area of the game. Depriving these areas of a fast travel connection aids the world building by labelling these zones as dangerous, remote, and hazardous. This zone gets slightly easier to navigate after the final boss is defeated and exclusion zone around Red Mountain opens up.

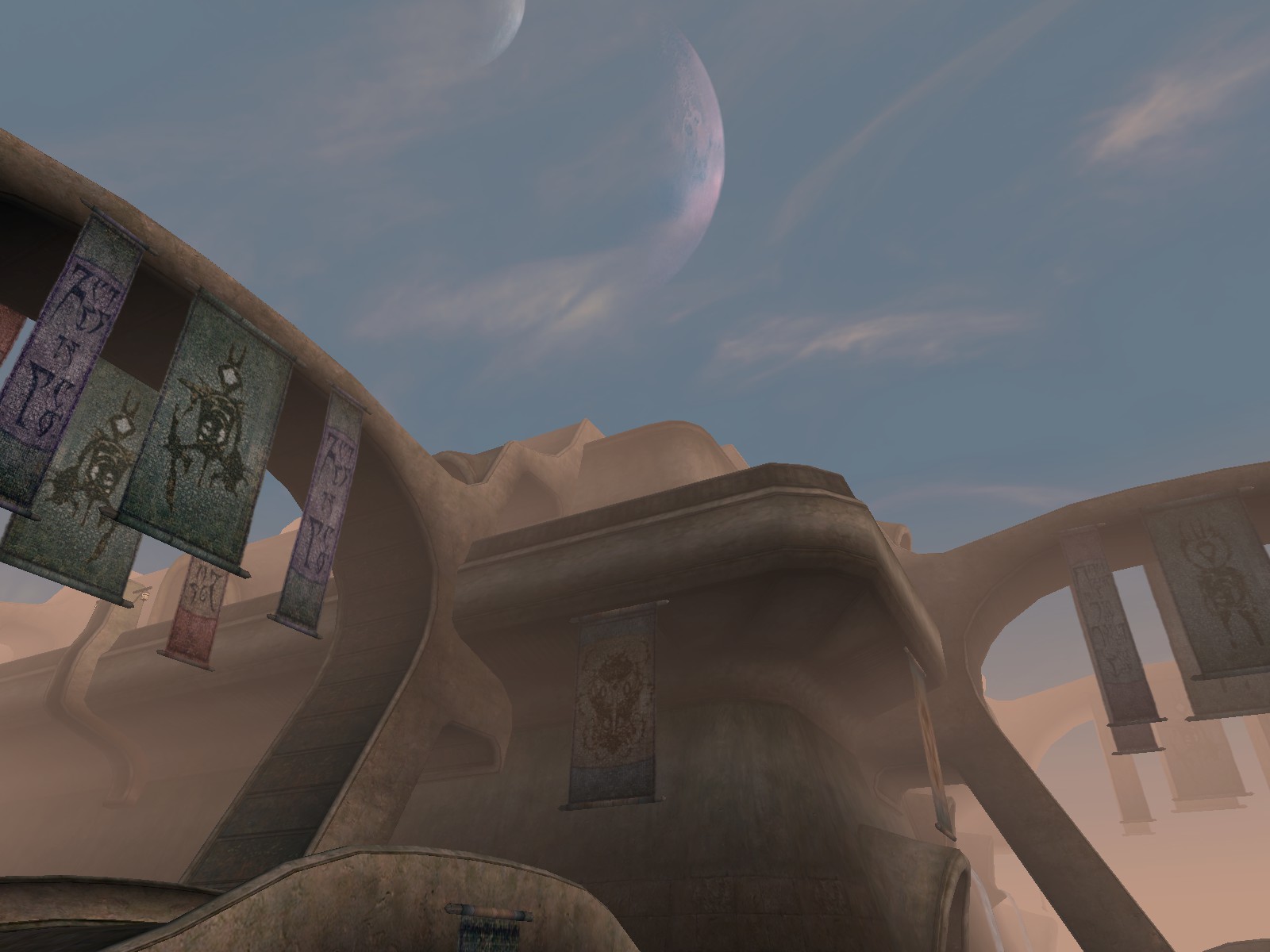

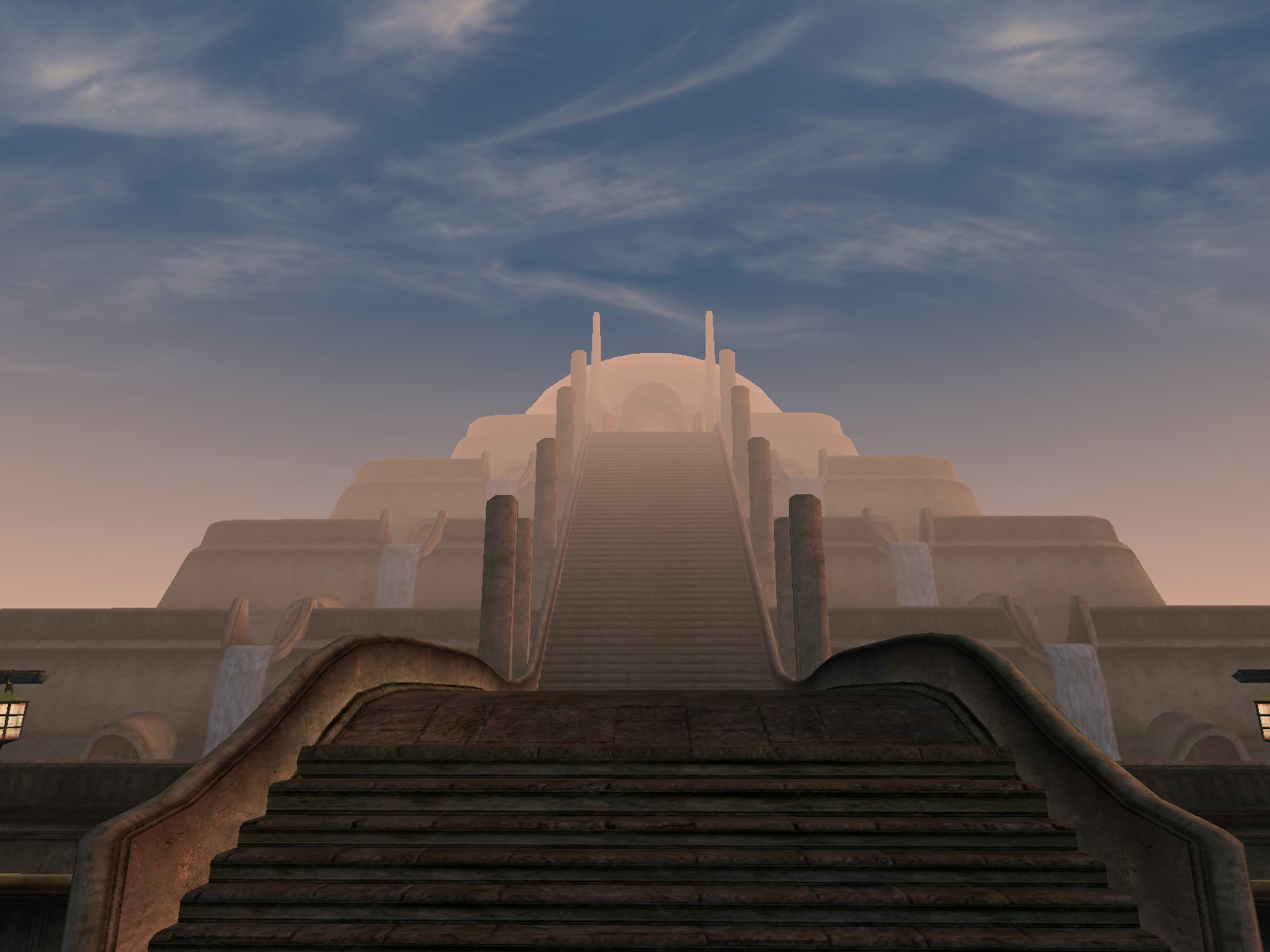

Dagoth Ur’s citadel at Red Mountain

Dagoth Ur’s citadel at Red Mountain

Very few people in Morrowind mention Red Mountain out loud, and they’re pretty cagey as to why. Combined with some of the more ominous random NPC dialogue (“There’s someone watching me. I can tell.”) and the austere presence of the Tribunal Temple religion creates a pervasive sense of foreboding that slowly encroaches more on the game world as the plot progresses. The lore, which is intimately tied to the world and narrative, becomes much more alluring as it becomes clear that crucial details in Morrowind’s history have been rewritten or hidden and that Morrowind’s forbidden knowledge is the key to uniting its past and future.

The Factions

“Games are a series of interesting decisions.”

— Sid Meier

Vvardenfell is ruled by three of Morrowind’s five (previously six) Great Houses: the honorable and knightly House Redoran, the cosmopolitan and mercantile House Hlaalu, or the eccentric and unscrupulous House Telvanni. These houses alternate between cooperative and hostile; the Houses have conflicting interests and each alternate between espionage, diplomacy, skirmishes, and sabotage to achieve them. Because the Tribunal outlawed open warfare between houses, Morrowind has a legal guild of assassins, the Morag Tong, that Houses hire to surgically resolve political disputes with minimal collateral damage.

Sadrith Mora, seat of House Telvanni and home to one of their many mushroom towers

Sadrith Mora, seat of House Telvanni and home to one of their many mushroom towers

Redoran council seat in Ald’Ruhn

Redoran council seat in Ald’Ruhn

The Hlaalu city of Balmora

The Hlaalu city of Balmora

Naturally, the player can only join one of these three Houses (without abusing bugs). This mutual exclusivity is yet another Morrowind feature that might seem intentionally obtuse, but significantly deepens the game experience in several ways.

First, this means that joining a House is a meaningful choice. Morrowind’s mutual exclusivity requires a player to seriously consider and commit to their choice of Great House, and each Great House has a distinct and flavorful identity for the player to engage with and roleplay. If there’s no opportunity cost to joining a faction, why wouldn’t a player just join all of them? Joining non-exclusive factions is functionally no different to ticking off a to-do list: Oblivion and Skyrim incentivize every player-character to be a warrior and a mage and an assassin and a thief in every playthrough. This is why choosing to join the Stormcloaks or the Imperials feels more important than any of the other factional choices: you can only choose one.

Second, it means that the world has easier and better ways to respond to the player’s choice. There are essentially only four possible alignments: Redoran, Hlaalu, Telvanni, and unaligned; if the player could join all three factions, then there would be a total of ten combinations that the designers would have to account for. The solution when there are so many possibilities is often to not respond to the player’s alignment: it’s why almost no one outside of the Companions or College of Winterhold seems to care or react if you join that faction or not, even though it’s supposedly an enormous commitment that everyone in the game world should care about.

Third, it motivates the player to learn about the world to make a more informed decision. If I have to commit to whichever House I choose for the rest of my playthrough, I’m going to do my research: investigate which resources the Houses offer, what their quests involve, what other groups (and other players!) think of them, and how they connect to other aspects of the game.

Finally, it aids the game’s role-playing elements dramatically. The Houses are very distinct: the Telvanni are crazy slave-driving wizards who live in mushroom towers, the Redoran are a pious order of warriors that fight in bonemold armor and live in big bug shells, and the Hlaalu are Empire-aligned merchants who manipulate Morrowind’s economy and politics from the vantage of their trade hubs. Each supports a clearly defined yet flexible playstyle and attitude, and their mutual exclusivity reinforces a character’s loyalty to one role.

This strategy for factions is a major reason that Fallout: New Vegas is so beloved; the whole game is mostly about managing different levels of involvement with mutually distrustful factions. It also means that mutual exclusivity between factions is one end of a spectrum of choices developers can make; good game design involves finding a sweet spot with complex relationships between factions.

The Narrative and Themes

“You need to learn to live with uncertainty.”

— my therapist

The Palace of Vivec in Vivec City

The Palace of Vivec in Vivec City

Morrowind’s religion, the Tribunal Temple, is perhaps its most dominant cultural force. The Tribunal consists of three mortals — Vivec, Almalexia, and Sotha-Sil — who became living gods through the use of ancient Dwemer tools during the Battle of Red Mountain. The Tribunal significantly revised Morrowind’s existing religion and replaced its previous patron deities, the three “Good Daedra”. Azura, one the displaced deities and the Daedric Prince of destiny and fate, prophesied that the martyred hero of the Battle of Red Mountain, Indoril Nerevar, would be reincarnated as the Nerevarine to right the Tribunal’s mistakes.

The overarching story is shrouded in layers of ambiguity. It’s never definitively settled whether the player is the “chosen one” or not. The game’s antagonist directly asks the player if they believe they’re the Nerevarine before the climactic final conflict; my favorite response, and the one I think is most truthful, is simply “I know no more than you do.” After the events of the main story, it’s unclear if the player fulfilled the prophecy because they are the Nerevarine, or if they are the Nerevarine because the fulfilled the prophecy, or if they were simply a pawn of Azura, the embodiment of destiny.

Whether the Tribunal obtained godhood virtuously or through deception is also ambiguous. The Tribunal’s account of the Battle of Red Mountain say that the hero Nerevar died from wounds sustained during battle, and obtained their divinity through their “superhuman virtue”. However, other credible accounts indicate that the Tribunal betrayed and murdered Nerevar, stole the Dwemer tools, and becoming gods in defiance of Azura. (This debate is appears to be definitively settled by a very well-hidden easter egg in the game.)

The friction between Morrowind’s unique indigenous culture, religion, and politics, and the directly Roman-inspired Empire — into which Morrowind was forcefully absorbed, and which stations troops throughout Morrowind — is a central theme in the story. Morrowind’s native Dunmer are extremely pious and xenophobic; this creates a potent source of tension when a foriegner, sent by the Emperor to act as an Imperial spy, appears to be the Nerevarine. The game’s antagonist, Dagoth Ur, is a fanatic who wants to establish a theocracy “to battle against the foreign animals who hold Morrowind in subjection”, “extirpate all remaining individuals of inferior and mongrel races from Morrowind”, expel the Empire, recover “ancient territories stolen” by Morrowind’s neighbors, and ultimately extend his religion “to all nations of Tamriel through subversion and conquest.” Despite this, Dagoth Ur’s backstory and dialogue make the character much more complex, even slightly sympathetic (although still obviously wrong), and significantly more memorable than almost any other Elder Scrolls character.

Here’s the really smart way that Morrowind ties all these things together: the game is about, among other things, joining and engaging authentically with a foreign culture. The game’s story follows the rough trajectory of:

- Navigating the xenophobia, racism, and suspicion of Morrowind’s people

- Learning about Morrowind’s culture, religion, history, and politics

- Uniting the Great Houses against Dagoth Ur

- Fulfilling the prophecy by defeating Dagoth Ur

Each of the gameplay mechanics I’ve mentioned previously — learning how to navigate Vvardenfell using the fast travel system, learning about the culture and world through the main story and side quests (such as joining a House), ultimately defeating the avatar of Morrowind’s xenophobia, and contributing back to Morrowind’s religion and culture — are the mechanical backbone of Morrowind’s story. Playing the game and getting better at it naturally complements the game’s themes and narrative. This is what you’d call “ludonarrative harmony” if you’re pretentious, and it’s one of the defining traits of excellent games.

Conclusion

“This is the end. The bitter, bitter end.”

— Dagoth Ur

The long-abandoned Dwarven ruin of Arkngthand

The long-abandoned Dwarven ruin of Arkngthand

Morrowind is at times held back by its technology, dated design, and classic Bethesda jank. (How much better would the game be if the draw distance let you see Red Mountain from everywhere on the map?) But the game’s strongest elements far outshine its flaws, and I was surprised at how many things like the lack of quest markers or the antique dialogue system ended up enhancing rather than detracting from the experience. It showed me that modern conveniences come at a hidden cost: in the quest to avoid complication, we often sacrifice complexity.

In light of all of these things, it’s no wonder that Morrowind has so much staying power, so many memes, and a project dedicated to a full rewrite of its engine. It’s a much more complicated game than its successors, but also complex in a way that modern games are afraid to be. Morrowind is not only a game worth revisiting, but a game worth being patient with and worth learning from.