Human Signal, Artificial Noise

We’ll All Be Happy Then. Harry Grant Dart, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

We’ll All Be Happy Then. Harry Grant Dart, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“How could an AI system seize control? There is a major misconception (driven by Hollywood and the media) that this requires robots. After all, how else would AI be able to act in the physical world? Without robotic manipulators, the system can only produce words, pictures, and sounds. But a moment’s reflection shows these are exactly what is needed to take control.”

— Toby Ord, The Precipice

I’ve been frustrated by the discussion around generative AI for some time now. The tech world insists that ChatGPT and Midjourney are revolutionary technologies that will change our society for the better, but I think the proliferation of generative AI has significantly reduced our quality of life. AI models across many domains are already enshrining inequality and making less free and equal, but I think the most immediately noticeable damage — that I see very few people substantively discussing — is being done by generative AI.

Generative AI first got attention when deepfakes became popular in 2017 and has infected every corner of our culture since the twin releases of ChatGPT and image generators like Midjourney in 2022. Microsoft, in their monk-like dedication to bloat Windows with every evil technology imaginable to man, recently introduced Copilot to Windows 11, and Google has recently followed with Gemini. I’m shocked at how positive the reception has been to generative AI and concerned that we’re accelerating towards generative AI rather than course correcting.

One obstacle in confronting generative AI has been that our collective imagination seems to be limited to Terminator: our only concept of AI harm is limited to an AI that achieves general intelligence and rapidly becomes much smarter than its creators and determines that to preserve itself, it must exterminate the human race. I love Terminator just as much as the next guy, but limiting our imagination to the premise of an 80s action flick has not only blinded us to much more grounded fears about AI, it’s blinding us to the harm that AI is doing right now.

First, it’s important to note that artificial intelligence is not intelligent. It does not see or understand text in the same way that we do: it essentially has been given a huge number of example conversations and guesses which words best continue the pattern (rather, the conversation) in a way that’s most similar to the examples it’s seen. That’s it. Nowhere in its training does it learn to judge or retain factual information or make informed decisions; it’s just babbling in a way that appears like speech.

In fact, its stupidity is one of its greatest liabilities: Air Canada trusted its chatbot to give advice to customers. Now they’re on the hook to give the discounts (for bereavement, no less) that the chatbot promised. An eating disorder helpline fired its workers after they unionized and replaced them with an AI chatbot that offered harmful advice. AI chatbots are notoriously mercurial and their answers to questions vary starkly with user phrasing, so it’s prone to giving biased answers — especially about conspiracy theories. It also frequently provides seemingly factual information that is actually utter nonsense. These chatbots don’t think, or even “see” text in the same way that we do. They do not understand anything that they have read or anything that users say. They are playing a glorified “continue the pattern” word game, and their use cases should be limited accordingly.

This is also not to mention the ethical concerns. AI has also been shown to blatantly plagiarize in multiple circumstances: the first cases were Microsoft’s Copilot generating code under a mistaken license, like reproducing verbatim the famous Quake III code for fast inverse square root — profanity and all — and claiming it was licensed under BSD2 with the wrong copyright holder. (The original Quake III code was licensed under GPL2.) Considering that it’s also spit out code under much more restrictive copyright, there are credible concerns that Copilot was trained on and reproduces copyrighted code. A similarly striking example is Midjourney almost exactly reproducing Steve McCurry’s famous Afghan Girl photo:

Midjourney reproduction of Steve McCurry’s Afghan Girl

Midjourney reproduction of Steve McCurry’s Afghan Girl

These are just a small sample of an ever-expanding list of cases where AI crosses from “inspiration” to blatant theft. But what goes around comes around, and students in high schools and universities around the world are plagiarizing from ChatGPT at epidemic proportions. Even university professors and researchers are getting in on it too: several papers, such as this one, were published with copy-pasted sections written by an apologetic ChatGPT that weren’t caught by the authors or editors. (As if we needed more proof Elsevier editors don’t read.)

This harm ranges from minor annoyance or inconvenience all the way to the society-level enshrinement of inequality, but the full scope is beyond what I can articulate in just one article. (You can start with Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O’Neil if you’d like a taste.)

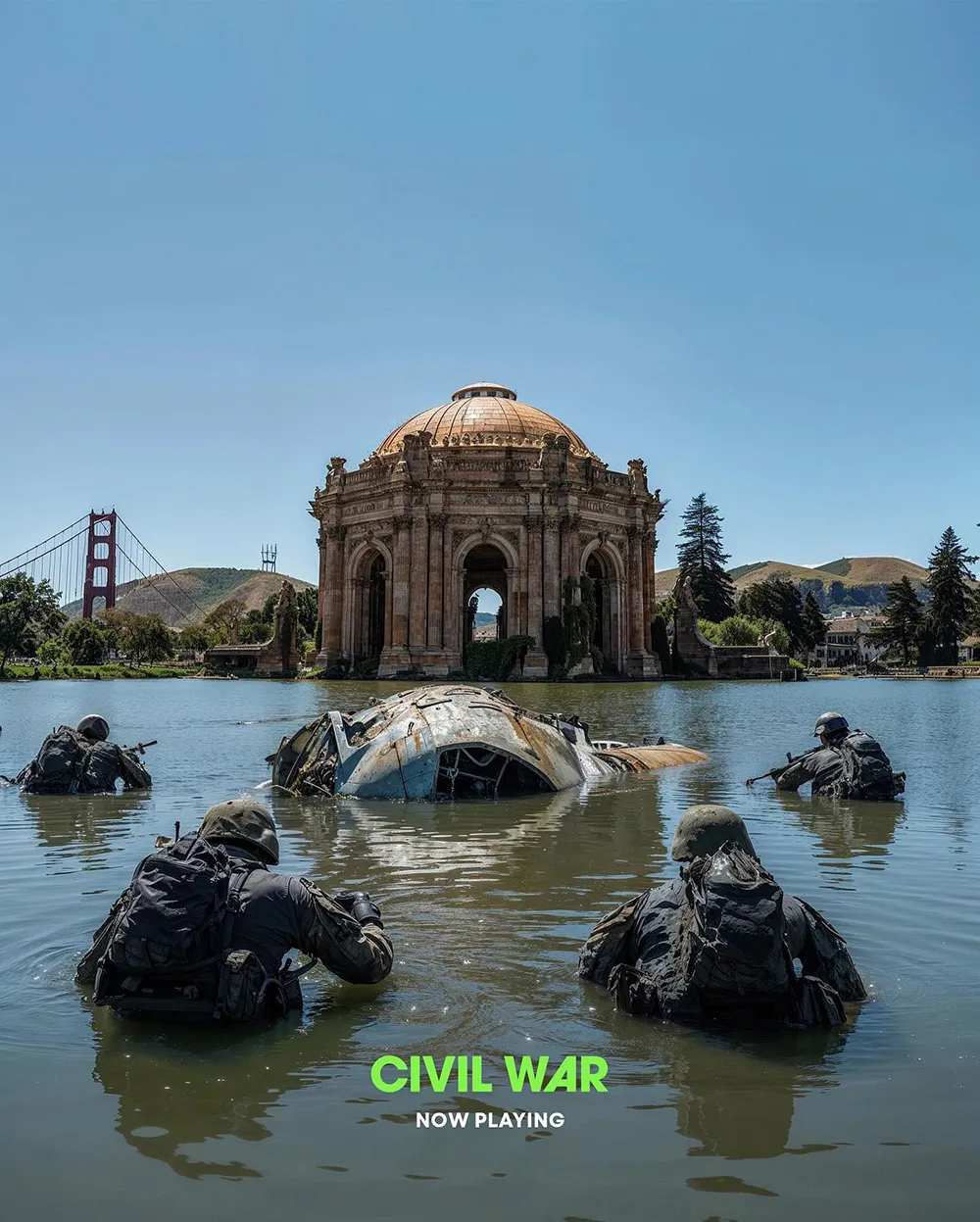

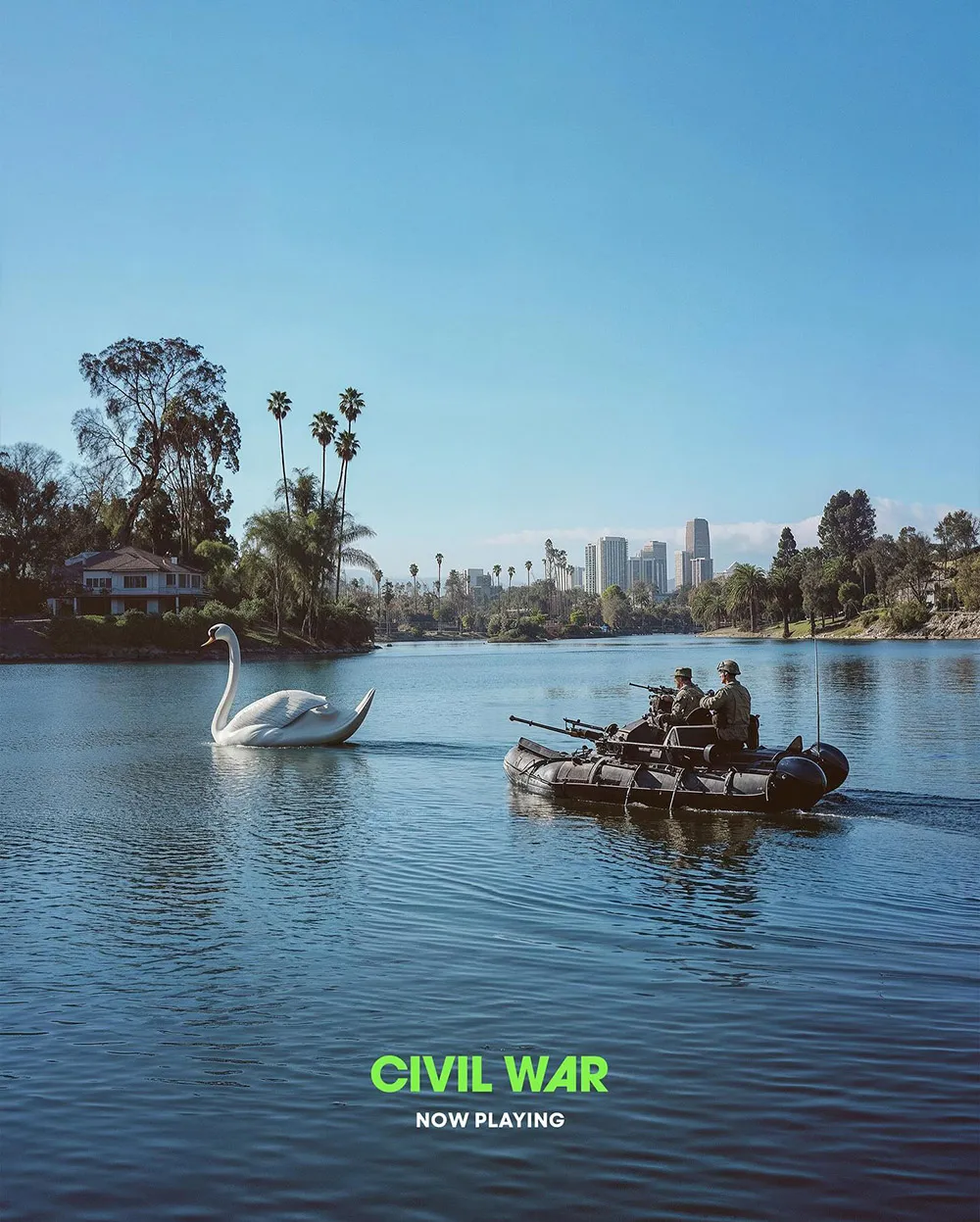

It’s probable that one day in the future, AI (with significantly different models from what we have now) will be capable of making art that is just as inspiring and high quality as anything a human can produce. Even if we were at that point (we obviously aren’t), Hollywood studio executives have no reservations about cutting corners with AI art wherever they can. For example, AI generated promotional art was used to advertise A24’s Civil War:

The Civil War posters in particular are a great example of the embarrassingly low bar that AI is held to; the posters seem passable if a bit bland at first, but they fall apart on a second glance. Why is the goose the same size as the gunboat? Why do the soldiers’ uniforms look like piles of dirty laundry? Why is there so much empty space?

AI posters also advertised Marvel’s Loki and generated the end credit sequences for Secret Invasion. I was interested in seeing Late Night with the Devil until I learned the title card images that appear multiple times in the film were AI generated, and I saw my frustration echoed in the top Letterboxd review:

Listen. There’s AI all over this in the cutaways and “we’ll be right back” network messages. For this reason I can’t enjoy the amazing performances and clever ending. It actually feels insulting when that skeleton message shows up repeatedly, like the filmmakers don’t give a shit and want to let you know that you’ll accept blatant AI in your 70s period piece. Don’t let this be the start of accepting this shit in your entertainment.

— based gizmo

If money or effort was conserved by using AI art, it did not result in a better end product. This is not a race to the top; it is a race to the bottom.

Naturally, a key term in Hollywood union negotiations this past summer was restricting the use of AI in art and movies; while WGA and SAG-AFTRA won guarantees that producers wouldn’t replace writers with AI, the writers themselves can still use AI and studios are allowed to train AI on the writers’ work. Actors are still concerned that loopholes may allow studios to scan and use their likenesses in film. For studio execs, the problem with making art is that too many humans were involved.

What AI has done to social media and search engines infuriates me on a daily basis. There are (at least!) millions of websites, wikis, and social media accounts that consist of nothing but the vacuous ramblings of unthinking automatons, strung together to steal our attention or scam us out of our time and money. (Previously, such content was mostly limited to the New York Times.) The only human effort involved in the manufacture of this trash is spent targeting these posts to search engines, so the object of every Google search is buried at the bottom of a content landfill dutifully supplied by ChatGPT.

All of this slop is maliciously designed to appear valuable enough to bait your click, steal your attention, and waste your time just to generate precious AdSense revenue. Hundreds of books written by ChatGPT have been listed on Amazon, a platform already flooded by ebook grifters. Every piece of AI-generated refuse is designed not only to be mistaken for authentic, purposeful, human-made content, but to choke it out like weeds in a garden. In the era ad revenue, attention is not just all you need; it’s all anyone even wants, and they’ll do whatever they can to get it.

As if there weren’t enough AI slop atop the results of every search query, Google and Bing have gone the extra mile to add AI summaries for every search. Frequently misleading if not just outright wrong, these hallucinations are often chased by equally nonsensical recommended searches that no human would ever bother to make. These all exist so companies like Google and Microsoft can squeeze the tiniest bit of extra user data out of every search.

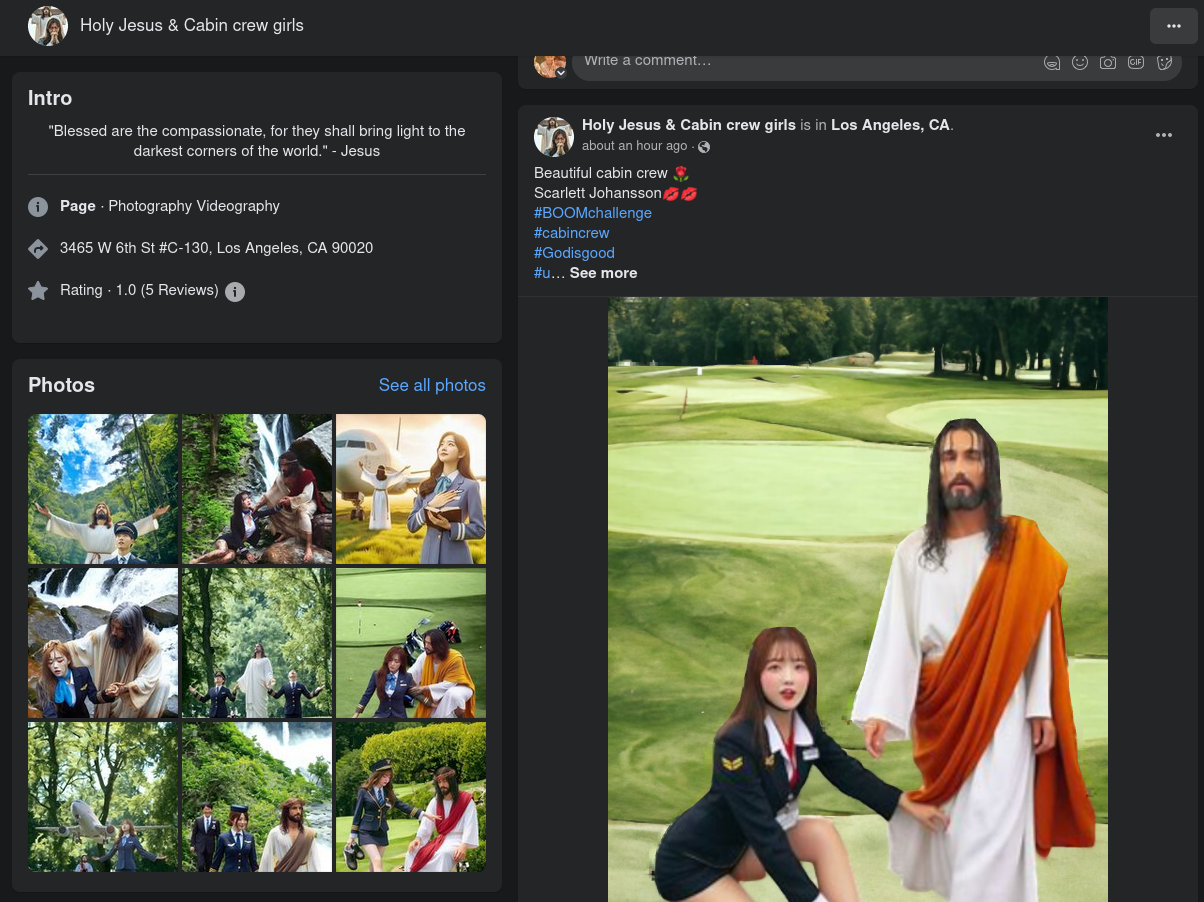

AI is already used to commit widespread elder abuse scams. An army of AI bots have flooded Twitter, either advertising or directly posting uncensored pornography as bait. Facebook is dominated by pages posting bizarre AI images featuring Jesus and airline flight attendants (among other weird mashups) designed to detect vulnerable marks. While writing this article, I opened Facebook and after less than a minute of scrolling my homepage was recommended that exact Facebook page.

The “Holy Jesus and cabin crew girls” Facebook Page

The “Holy Jesus and cabin crew girls” Facebook Page

There are two crucial problems in detecting AI images and videos. The first is that an observer has to actually know what to look for: waxy skin, misshapen fingers, incorrect lighting, distorted backgrounds, scrambled text, and so on. Even in the absence of these obvious flaws, there might be “higher-level” signs: people or objects might be positioned in ways that don’t make sense (frequently, a person standing in the middle of the street), the perspective might not make sense, and so on. Here’s a particularly exaggerated example:

The hands, teeth, skin, eyes, shoulders, arms, yellow dress, and necks are mangled and misshapen. The lightspots on the clothes and skin seem to disagree. However, detecting these flaws is usually much harder, especially to an untrained observer. Even a trained observer might let subtler blemishes slip by if they’re tired, in a hurry, or just don’t know that they need to look.

The second point is that these flaws obviously have to be present in the first place. It’s not possible to fix every AI hallucination with our current techniques, but a malicious actor doesn’t need to: generating images is so easy that sooner or later an AI will produce an image without detectable giveaways, or with flaws that can be edited out easily enough. Audio deepfakes are even harder to detect than video deepfakes, especially considering that the script and training audio can easily be selected to avoid any telltale audio artifacts.

The mass production of garbage is hardly new. Theodore Sturgeon coined Sturgeon’s law — “ninety percent of everything is crap” — in the 50s. My point is that it’s never been so easy to make crap, and it’s never been so easy to make crap that appears like it’s not crap. The end result of the explosion of AI that the archipelago of valuable human content is being drowned in an ever-deepening ocean of AI-generated sewage, infested with anglerfish swimming just below the surface.

But there are even more malicious uses of AI than just churning out content. Despite not being advertised so strongly (since regulators responded in 2019), deepfaking software is widely available and possible to run on a personal computer. It’s so easy that they became internet memes: deepfake people to sing a song from the Yakuza games, or create hours of deepfaked videos of Joe Biden and Donald Trump playing Minecraft. Almost immediately, celebrities like Scarlett Johansson, Taylor Swift, and Emma Watson had their likenesses deepfaked into pornography. It has never been easier to manufacture realistic disinformation, blackmail, scam bait, or harassment material, and I’m worried it’s inevitable that I or someone I care about could be a victim. Even if everyone who sees it — maybe coworkers, family, friends, or total strangers — immediately knows that it’s fake, that doesn’t negate the psychological harm of seeing oneself inserted into a pornographic or violent photo or video.

Obviously, deepfakes have already been used to edit politicians into more than just Minecraft videos. It was possible to serve up targeted election disinformation before ChatGPT and Midjourney (who remembers Cambridge Analytica?), but falsifying images often took several hours of skilled labor to create something convincing, and faking videos often took hundreds of man-hours; an AP news article on election disinformation summarizes it succinctly:

[Generative AI] marks a quantum leap from a few years ago, when creating phony photos, videos or audio clips required teams of people with time, technical skill and money. Now, using free and low-cost generative artificial intelligence services from companies like Google and OpenAI, anyone can create high-quality “deepfakes” with just a simple text prompt.\

The article cites AI generated disinformation being used in several countries — in one example in Taiwan, impersonating a US House Representative to trick voters into believing that the US would provide more aid if the incumbent party remained in power. Midjourney has blocked photos including Trump and Biden,, but plenty of AI election disinformation featuring them has already been generated. Even if Midjourney specifically can prevent election disinformation from being generated on their platform, a state-funded propaganda studio could easily create a similar tool.

Unfortunately, this technology is here to stay. The techniques used in generative AI are public, scientific knowledge. Deepfakes are regulated in the US, but it’s still legal and feasible to make, download, and run deepfake software on a personal computer — it’s just using it the wrong way that’s illegal. Other generative AI like ChatGPT and Midjourney currently aren’t feasible to run (and definitely not to train) on a home computer because of astronomic hardware and energy costs, but it will be in the future as techniques and hardware inevitably get more efficient.

Watermarking AI content won’t help: it’s impossible to enforce, so a malicious actor refusing to watermark their content will make it appear more legitimate. It’s also not possible to write an algorithm or design another AI to differentiate between real images and fake ones; everything that can be captured by a camera can be replicated by a computer.

Our best hope for reigning in AI — as much as we still can — is to drop the far-off fantasy of AI as an intelligent adversary and recognize it as a tool that is prone to misapplication and enables widespread scams, deception, and antisocial behavior. AI does not need a robot army to hurt us; it also doesn’t need to be sentient, or even smart. It just needs to be misunderstood, misapplied, and misused. Unfortunately, the wisdom of Upton Sinclair echoes: it’s difficult to get AI evangelists to understand the dangers when their salaries depend on them not understanding it.

I worry that this is only the beginning. Crucially important photos and videos may no longer be accepted by the press or admissable in court because they can no longer be trusted to be authentic. Even worse, AI could sway juries into wrongful convictions or dupe overeager journalists into spreading propaganda. I worry that AI has already done permanent damage to our ability to discern what is true and false, and politicians, businesspeople, and researchers are too financially interested to turn away. We are already living in the AI post-apocalypse, and the fallout has only just started to reach us.